| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

Lectures / 20/07/2009 7:30 pm

Communication?

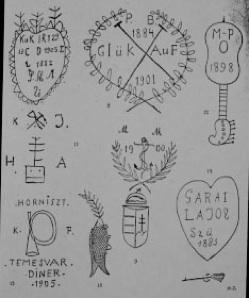

‘Speaking Scars’. What did Tattoos tell Criminologists in 19th-century Europe?

This lecture will discuss the relation between early 19th-century projects of civil and criminal identification and subsequent criminological debates about the existence and characteristic signs of a ‘criminal type’. The paper first discusses investigations by French forensic scientists in the mid-19th century into physical marks of occupation: deformities and discolorations of the hand and other parts of the body caused by prolonged activity in particular trades, and tattoos with conventional symbols denoting specific occupations (e.g. tailor, smith). It goes on to explain the prominence of the tattoo in the 1880s/90s debates among criminal anthropologists about the ‚meaning’ of criminals’ tattoos. Unlike other alleged signs of criminality – anomalies of physique, anatomy etc. – the tattoo is not hereditary or innate but intentionally acquired. This apparent paradox can be illuminated (if not entirely resolved, given the vexed and murky relationship between acquired and congenital characteristics in this period) by considering the extent to which the tattoo came to figure as the occupational sign of criminality.

The presentation will be in english.

continuative Links:

Bibliography:

- Philippe Artières, À fleur de peau. Médécins, tatouages et tatoués (2004)

- Peter Becker, Dem Täter auf der Spur. Eine Geschichte der Kriminalistik (2005)

- Claudia Benthien, Haut. Literaturgeschichte, Körperbilder, Grenzdiskurse (1999)

- Jane Caplan, ed., Written on the Body. The Tattoo in European and American History (2000 )

- Willam Carruchet, Bas-fonds du crime et tatouages (1981)

- Steven Connor, The Book of Skin (2004)

- Margo DeMello, Bodies of Inscription. A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community (2000)

- Juniper Ellis, Tattooing the World. Pacific Designs in Print and Skin (2008)

- Alfred Gell, Wrapping in Images. Tattooing in Polynesia (1993)

- Steve Gilbert, Tattoo History. A Source Book (2000)

- Valentin Groebner, Der Schein der Person. Steckbrief, Ausweis und Kontrolle im Europa des Mittelalters (2004)

- Nina Jablonski, Skin. A Natural History (2006)

- Makiko Kuwahara, Tattoo. An Anthropology (2005)

- Stephan Oettermann, Zeichen auf der Haut. Die Geschichte der Tätowierung in Europa (1994)

- Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, 3 vols.

- Adolf Spamer, Die Tätowierung (1933; reprint 1993)

- Nicholas Thomas et al., eds., Tattoo. Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West (2005)

- Christian Warlich, Tätowierungen. Vorlagealbum des Königs der Tätowierer, hrsg. von Stepna Oettermann (1981)